Second Careers: Is it too late?

Ruminating on second chances, late bloomers, and learning new skills when you're older

I recently had a conversation with a slightly younger friend of mine, who revealed that they had begun thinking about making plans to have children. They weren't yet ready, but they had realized that they wanted children, and that their life would have to be rearranged and money would have to be made in order to facilitate this. We realized that both of our parents had had children by the time they were our age. My mother was, in fact, already on her second marriage.

When I turned 24, I had a moment of bitterness when I figured I could no longer claim to be "in my early twenties." (Technically, I reasoned, I was in my mid-twenties — quelle horreur!) I also had no career accomplishments to speak of, was pretty broke, and had just split up with a serious boyfriend. My dad was already working as a journalist at 24. He would go on to a brightly successful international career at Time magazine.

Leaving aside such childhood factors that impact your innate drive for success — everyone has them, good and bad — we should divorce ourselves from the concept that if we don't make it young, we don't make it.

Thomas Curran and Andrew P. Hill, the authors of a 2019 study on perfectionism among American, British, and Canadian college students, have written that “increasingly, young people hold irrational ideals for themselves, ideals that manifest in unrealistic expectations for academic and professional achievement, how they should look, and what they should own,” and are worried that others will judge them harshly for their perceived failings. This is not, the researchers point out, good for mental health.

Margaret Talbot, The New Yorker

Additionally, we have the looming, inexorable social media machine to avoid, if we want to dodge comparison — internal or external — with our seemingly more settled and successful peers. But what's the story here? Are we really doomed?

Well ... not really, but we do think a little slower. Our "cognitive decline" can begin in our twenties. Apparently, air traffic controllers are made to retire at the age of fifty-six, because our literal mental processing speed slows down. The tradeoff, however, is that our intelligence deepens:

“Our brains are constantly forming neural networks and pattern-recognition capabilities that we didn’t have in our youth when we had blazing synaptic horsepower,” [Rich Karlgaard ] writes. Fluid intelligence, which encompasses the capacity to suss out novel challenges and think on one’s feet, favors the young. But crystallized intelligence—the ability to draw on one’s accumulated store of knowledge, expertise, and Fingerspitzengefühl—is often enriched by advancing age.

Margaret Talbot, The New Yorker

One point that Talbot brings up is "the sensation of being an absolute beginner." It's uncomfortable. It opens you up to indignity. It can be an intensely humbling experience. But she also points out:

Starting all over at something would seem to put you right back into that emotional churn—exhilaration, self-doubt, but without the open-ended possibilities and renewable energy of youth. Parties mean something different and far more exciting when you’re younger and you might meet a person who will change your life; so does learning something new—it might be fun, but it’s less likely to transform your destiny at forty or fifty.

Margaret Talbot, The New Yorker

The truth is, we are more settled when we get older, and less likely to do something that could disrupt our lives. There are things to lose — relationships, children, jobs, dignity. It is uncomfortable to start over. And it's often seen as shameful.

We've got to reckon with our ability to feel discomfort — because there are two specific kinds of discomfort (Okay, there are lots of different kinds of discomfort, but I'm mentioning these two): There is the kind that you feel when you are learning or developing a new skill. And there is the kind that you feel when you are being limited in your life.

The two are not the same!

Why do we feel the pressure to stop growing once we reach a certain age?

I won't recount the entire article by Margaret Talbot — it is definitely worth reading — but I did want to point out two things:

- This stunning set of facts: "Annie Proulx published her first novel at the age of fifty-six, Raymond Chandler at fifty-one. Frank McCourt, who had been a high-school teacher in New York City for much of his career, published his first book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir Angela’s Ashes, at sixty-six. Edith Wharton, who had been a society matron prone to neurasthenia and trapped in a gilded cage of a marriage, produced no novels until she was forty."

- It is good for the soul to keep expanding and growing: "Many of us are wary of being dismissed as dabblers, people who have a little too much leisure, who are a little too cute and privileged in our pastimes. This seems a narrative worth pushing back against. We might remember, as Vanderbilt points out, that the word 'dilettante' comes from the Italian for 'to delight.'" In other words, the delight that one finds in continued learning keeps our brain working. It can even help stave off Alzheimer's and dementia.

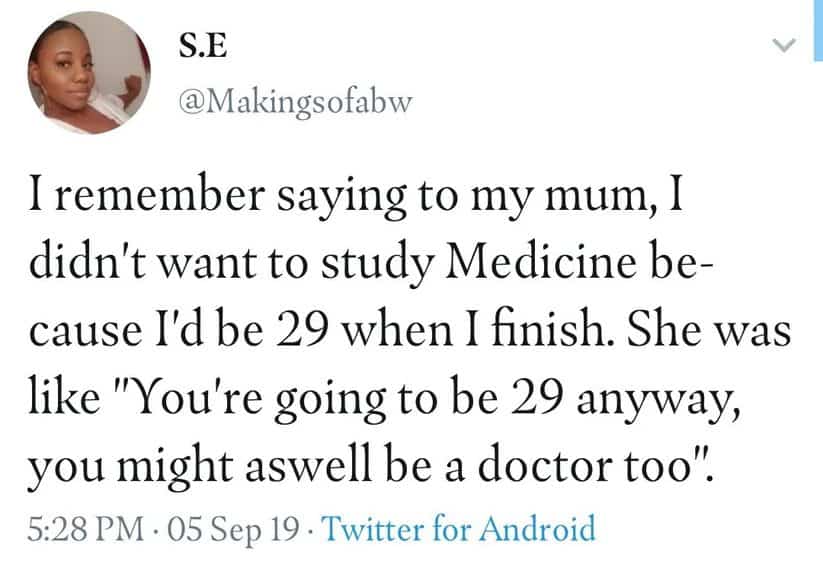

It's true — it is much, much easier to break out of your mold when you are younger. But it's not impossible to do so as you age, and let us not forget this inalienable fact, as presented by an anonymous Twitter sage:

Hi! I'm Piya. I'm a freelance creative starting a new career, and I want to help you start yours, too.