Living Your Life vs Enduring it

There's a well-known meme of Leonardo DiCaprio in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood where he's pointing at something in recognition. He's excited. He knows what the speaker is talking about.

That's how I felt while I was reading this recent article by Kyle Chayka in The New York Times, "How Nothingness Became Everything We Wanted". The — feeling? The zeitgeist? Widespread malaise? — that it describes is probably most closely associated with Millennials, along with our trademark depresso-humor.

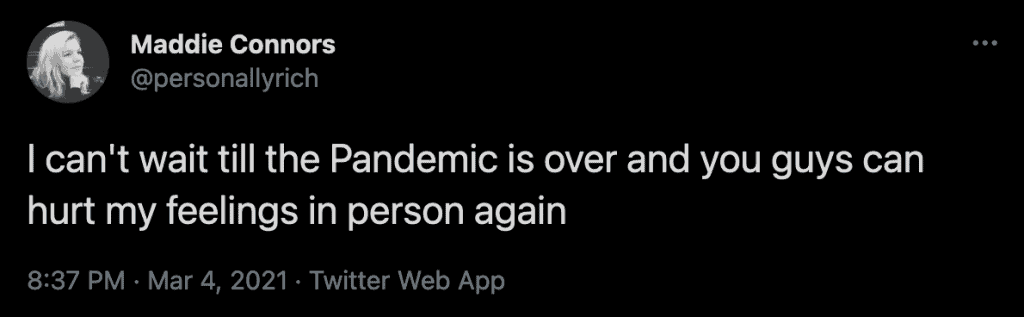

We've got so much to deal with these days. Omnipresent (and omnipotent) social media, a relentless news cycle, financial insecurity, an aggravating government — even before the pandemic, we wanted out. Like, how did we get signed up for this, exactly? Why is life so hard?

... these moments of tumult also inspire retreat. Climate change, technological upheaval, racism, inequality — the churn of history, which shows no signs of stopping — these all make it easy to instead slip into the welcoming void of the content stream. Numbness beckons when life is difficult, when problems seem insurmountable, when there is so much to mourn.

Kyle Chayka, The New York Times

I spent a lot of early quarantine seesawing between utter relief at the disruption of my daily life, and stress about "what I was going to do" with all of this. Something had to be done, of course, but what? Could I, recently cut loose from a full-time job, change my life? How could I possibly face another 9-5 job when all this was going on? Did I really want to start a second career during this mess?

Don't get me wrong — I was incredibly lucky. I qualified for unemployment, and my living situation was stable. I don't drink alcohol regularly. I had a fluffy little cat, no familial obligations, and I lived in the same building as one of my best friends. I'm not trying to discount the struggles of others. But I will say this: the monumental disruption of my daily life — the enforced numbness and disconnection — showed me how much I needed to change, how much I could not face going back to my previous life.

No one seems to want anything; there is no enthusiasm for desire in this culture, only the wish that we could give it up. It’s an almost Buddhist rush toward selflessness with the addition of American competition and our habit of overdose: as much obliteration as possible.

Kyle Chayka, The New York Times

Which brings me to the title of this post. When, exactly, did we stop living? Did you live during your high school years? Were you living during college? What was the point, where was the point? Since when did Millennials, formerly derided as self-involved narcissists, turn into such sad-sack Gen X-ers?

I can't write about "living for yourself" without acknowledging the responsibility this bears. There's no glory or satisfaction in taking without giving, in my opinion, but in order to give, what must you take? What are the boundaries you must settle in your life in order to start clearing the way for a new path? Boundaries like:

- How much TV you watch

- How much non-professional time you spend on social media

- How much time you spend on personal or romantic relationships that drain you

Here's the thing. You could, theoretically, just grind through your life, taking the free time that is allotted to you and using it to indulge in Call of Duty or World of Warcraft. You can obliterate entire weekends on Netflix. You want romantic validation? You don't even need to go to a bar and engage in the taxing reality of interacting with other humans — you can just call up Tinder and do some no-stakes flirting for another hit.

But think about this: in ten years, fifteen years, someone will ask you what you did with your life. They will ask you if you did something real. And I'll admit it right now: Yes, I am a snob about activities. And yes, I will absolutely tell you that there is a difference between pursuing a skill and playing Call of Duty every weekend for ten years. I don't want "playing Call of Duty" for ten years to be my answer, do you?

What have you done lately that's "real"?

Hi! I'm Piya. I'm a freelance creative starting a new career, and I want to help you start yours, too.